Dialogue systems represent a much more interesting architectural problem than it may first appear. They show up in seemingly simple contexts like support chatbots, as well as in notably more complex environments, such as video games.

In this article, I want to pose some reflections on the appropriate architecture for building a dialogue system that can grow without collapsing under its own weight. When we tackle software development, we usually start from a set of requirements that rarely remain stable. The difference between a sustainable system and a technical nightmare often lies in a fundamental question: in what direction is it reasonable for this system to grow in the future?

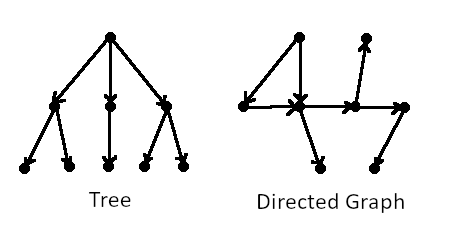

From tree to graph

The most immediate mental model for a dialogue is a tree: we start from the root, and as the user makes decisions, we descend down different branches until we reach a leaf, an ending. This approach works for trivial cases, but quickly introduces structural limitations. A tree imposes a rigid directionality where moving forward is simple, but moving back or reusing fragments is not.

To achieve real flexibility, the dialogue must be modeled as a graph with various nodes connected to each other.

Specifically, we will want a directed and weakly connected graph:

- Directed, because transitions between nodes have a defined direction. Being able to move from node A to B does not mean one can move from B to A.

- Weakly connected, because all nodes are connected if we ignore directions, and there are no isolated nodes. All nodes belong to the same dialogue, even if there isn’t necessarily a path from A to B and from B to A.

This conceptual change is what will allow the system to grow organically.

Structural validation

Modeling the dialogue as a graph allows us to introduce something that is rarely done correctly: the possibility of structural validation. A dialogue should not be deployable if it contains inaccessible nodes, and detecting this requires a simple approach:

- We convert the directed graph (each dialogue) into an undirected graph, removing the representation of direction.

- We traverse the graph from the initial node and verify that all nodes are accessible. For this, we can create a list of visited nodes containing the initial node and another list of checked nodes. We recursively explore visited but unchecked nodes, adding to the visited list any nodes we can reach from there.

- We stop when we confirm that our visited list contains all dialogue nodes, failing if after visiting all, we are missing any, since this would mean the dialogue is incomplete or poorly defined.

Node representation

The worst possible option, while surprisingly common, is to program a class by hardcoding dialogues directly by using monolithic structures, endless switch statements, or nested conditionals based on numerical identifiers. This approach does not scale, is not maintainable, and turns any change into a high-risk operation. As soon as the dialogue ceases to be trivial, the system becomes unmanageable.

A sustainable architecture begins by separating content from behavior.

The ideal, then, is to store dialogue nodes as data: JSON, YAML, XML,… even with individual files per node. This last option is especially convenient for editing, debugging, and version control, although nothing prevents them from later being transferred and loaded from a database if our system’s characteristics make it more convenient.

Thus, a simple example of a node in JSON would be:

firstNode.json:

{

"id": "firstNode",

"steps": [

{ "type": "line", "speaker": "Ticket Inspector", "text": "Tickets, please" },

{ "type": "line", "speaker": "Player", "text": "Tickets?"},

{ "type": "line", "speaker": "Ticket Inspector", "text": "Don't make me repeat myself, please" },

],

"options": [

{

"text": "Oh yes! One moment, please.", "next": "endGood"

},

{

"text": "I don't have to show you anything!", "next": "endBad"

}

]

}Each node contains a sequence of steps that are executed in order and a set of options that determine the next node the conversation can go to. In the example, depending on the chosen option, it jumps to the node “endGood” or “endBad”. The dialogue thereby ceases to be code and becomes a navigable structure.

endGood.json:

{

"id": "endGood",

"steps": [

{ "type": "line", "speaker": "Player", "text": "Here you go." },

{ "type": "line", "speaker": "Ticket Inspector", "text": "Thank you very much."},

{ "type": "end" }

]

}In this system, each of the steps has an associated type and a series of optional additional fields that depend on the type. In a minimal system, two step types are enough:

line, which displays a line of text.end, which ends the conversation.

This decision is strategic because defining steps as types allows the system to grow without needing to be rewritten and without new types affecting existing ones. The system’s complexity can thus increase easily to adapt to future requirements.

In our video game example, greater complexities can easily emerge. We might encounter:

- Visual or sound events accompanying the dialogue.

- Checks of the world state, so NPCs (Non-Player Characters) react to their surroundings.

- Automatic decisions dependent on external variables present in the characters, like their relationship status (ally, neutral, hostile,…).

- Random rolls or skill checks to decide if the player succeeds at something. Consider a “persuasion” skill determining whether or not the NPC is convinced.

The important thing here is that even if we want to add these new considerations, the architecture doesn’t change; only the catalog of available steps expands.

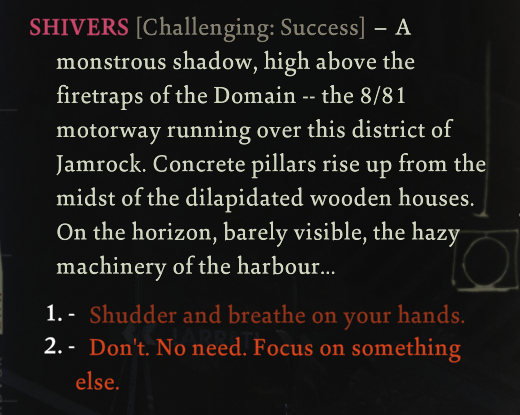

Dialogue and choice example (Disco Elysium)

Class architecture

Regarding class architecture, a clean separation could start with a distinction into two blocks: one with the data structure used to represent dialogues, and another with management classes.

Data representation would be handled by these classes:

DialogueGraph: Represents the complete dialogue as a graph. It would hold a list of nodes (DialogueNode), as well as a reference to the initial node.DialogueNode: Class representing a graph node. It would have an identifier, a list ofaDialogueStep, and a list ofDialogueOption.aDialogueStep: Abstract base class for all step types. Concretely, in our example, we would haveDialogueStepLineandDialogueStepEndimplementing this abstract class and some method to obtain the dataset specific to each step type (the speaker, the name of the sound effect, etc.).FactoryDialogueStep: Since the data to be stored in each step is different, we should have a factory that returns anaDialogueStep, generating one type of step or another depending on the step type and saving the relevant data in the appropriate class. To avoid needing a Builder class for the step-type-specific data, we could pass as a creation parameter a DTO with the step’s content from the JSON.

On the other hand, the management classes:

DialogueLoader: Dedicated to loading dialogue data and transforming it into aDialogueGraphtype class. That is, its job is to translate the JSON into our internal format.DialogueManager: This class manages the dialogue state, including the node where the user is and the current step within that node, as well as state change mechanisms.DialogueUI: With this class, we would handle on-screen presentation.

Combining state management and presentation can be tempting, but it’s a classic mistake that limits future evolution. Both responsibilities must be separated.

Designing for what doesn’t yet exist

With this foundation, we would have a robust yet flexible system for representing complex conversations in weakly connected graphs, allowing us to handle a huge variety of situations without having to redo the underlying architecture itself. It’s not about implementing all possibilities from day one: what we want is to design a system capable of absorbing them when they appear.

Dialogue systems, like so many others, fail when they become unmanageable due to an architecture that doesn’t admit change. Thinking of them as graphs, separating logic, and isolating responsibilities, far from academic over-engineering, means designing in a way that anticipates their evolution, assuming that all worthwhile software will grow and change sooner or later.